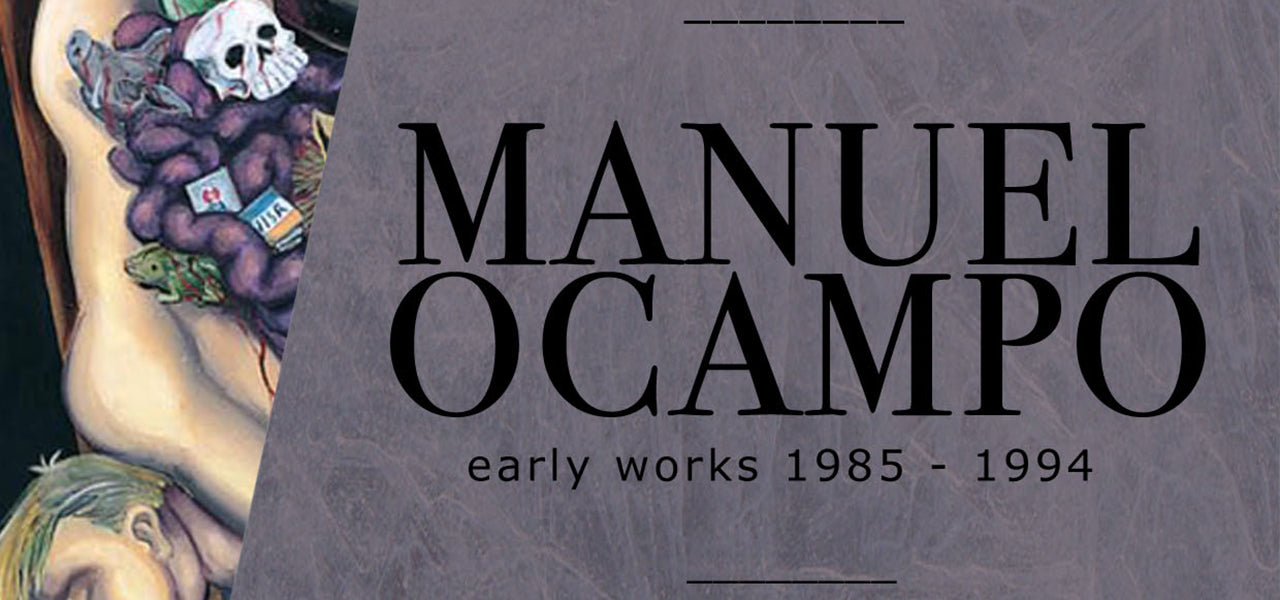

Manuel Ocampo Early Works 1985 - 1994

MANUEL OCAMPO

13 FEBRUARY - 20 APRIL 2017

-

With a career spanning 30 years, Manuel Ocampo has forged a path of (meandering) resistance in the international art circuit. Born and raised in the Philippines, he migrated to the US, graduating from college in California, where he used to be based for almost a decade. His first solo show at La Luz de Jesus Gallery in Los Angeles in 1988 brought him unprecedented attention in the international art scene; cemented further by his inclusion in two prominent European art events : Documenta IX (1992) and the Venice Biennale (1993). He will be featured once again in this year’s edition of the Venice Biennale (under the curatorial program of Joselina Cruz for the Philippine Pavilllion). He has subsequently participated in numerous museum exhibitions and biennials around the world, including the biennials of Gwangju (1997), Lyon (2000), Berlin (2001), and Seville (2004). Consistently exhibiting and organizing exhibits in and outside the Philippines, noteworthy of which is the series Bastards of Misrepresentation and Manila Vice in Sete, France.

Manuel Ocampo emerged at the time when postmodernist art was coming to a close giving way to an urgent voice that sought to level the cultural field through the representation of the other, landing in California after leaving the country right after the People’s Power Revolution in 1986. Living under Martial Law and being schooled by Catholic priests where he was trained to make copies of devotional retablo paintings, within such aforementioned circumstances “he wrestled with the trinity of the spiritual (Spain), the material (U.S.), and the self (Philippines).” Within this conflicting triumvirate, he has created an equally iconic visual idiom that mixes high and low, academic and popular, sacred and secular images that resound overt commentaries on religious and social taboos, race, oppression, language, and geopolitics.

The works from his early period well represented in this exhibition bear influence that are discernible in the paintings of younger contemporaries such as Robert Langenegger (the scatological Catholic imagery and political cartoon type of depicting racial tensions), Jayson Oliveria (the non- hierarchical use of images and texts), Louie Cordero (the explosion of colours), Dina Gadia (the patina of nostalgia of sourced images, mostly ads and cartoons from post-war mid-century); and in his own contemporaries who are based in Manila such as Romeo Lee (the over-all grotesquerie), and Gerardo Tan (the layering of images and erasures/defacements that reveal the conceit of an artwork being foremost a painting than a language or a political stand). It’s no coincidence that these artists were also part of the multi-city travelling exhibit Bastards of Misrepresentation out of a psychic affinity and convivial friendship.

-

Subject of a retrospective hosted by Archivo 1984, the bulk of these artworks have been repatriated from the collection of Track 16 Gallery and collector Tom Patchett in San Diego, USA. Complemented by a few finds from local private collections, this will be the first time that these works will be exhibited here in the Philippines and is the first ever significant show of Ocampo’s notorious early period that the country will be able to scrutinize.

It’s a timely and apt homecoming in light of recent global political events that appears to have reverted to how it was thirty years ago, at the dawn of a Perestroika and Glasnost, as the roots of multiculturalism began to emerge with the promise of a utopian Benetton world. Despite the altruistic aims of such an aspiration, its unraveling had been vested much in its very liberalism, its unintended consequences the unbridled hold of big business almost taking stead already of the state. What was the voice of multiculturalism shouting dissent against neo-colonial homogeneity has been umbraged into a market stranglehold, and with it the double-edged blessing of market expansion into the art world. Yet how can artists live with this paradoxical guilt of making political critiques against this system where they make money from? Ocampo, knowingly and/or queasily inserts himself in this paradoxical dilemma, playing the game, as he’d rather see it, playing the identity politics card, and acing it in a luck of the draw. Yet he bemoans that dilemma : “it’s harder to forget than it is to remember.” – an identity that catches up with him in his nomadic state, forever in exile, treading through his own path of resistance before the world gets totally walled in by tyrannical philistines.

- Lena Cobangbang